Fight against caste-based discrimination in The Gambia: A tale of repression of and resistance by the Communities Discriminated on Work and Descent

In the long-standing resistance against a socially stratified society in the West Africa region, and particularly in the Upper River Region (URR) of The Gambia, a legal case and the following High Court judgement brought to light the persistence of caste practices and associated discrimination based on work and descent in the region.

Case Citation: Allegae Modi Trawally vs. Governor of Upper River Region

Date of Decision: December 15, 2022

Laws referred: International as well as National both.

Introduction

In their fight against being labelled as “Slaves” and being forced to live as such in a caste-based social order, the members of this social group in the URR had written to the Governor of the region and Former President Yahya Jammeh in 2016. They sought action on the violation of their human rights, however, got no response from them. Subsequently, they resorted to the court for the matter to be addressed using the 1997 constitution of The Republic of The Gambia. These events, that unfolded in the midst of the years 2021 – 2022, tell a story of the oppressed caste, in this case, the so-called “Slave” class resisting the practice of discrimination and exclusion by the dominant “Noble” class.

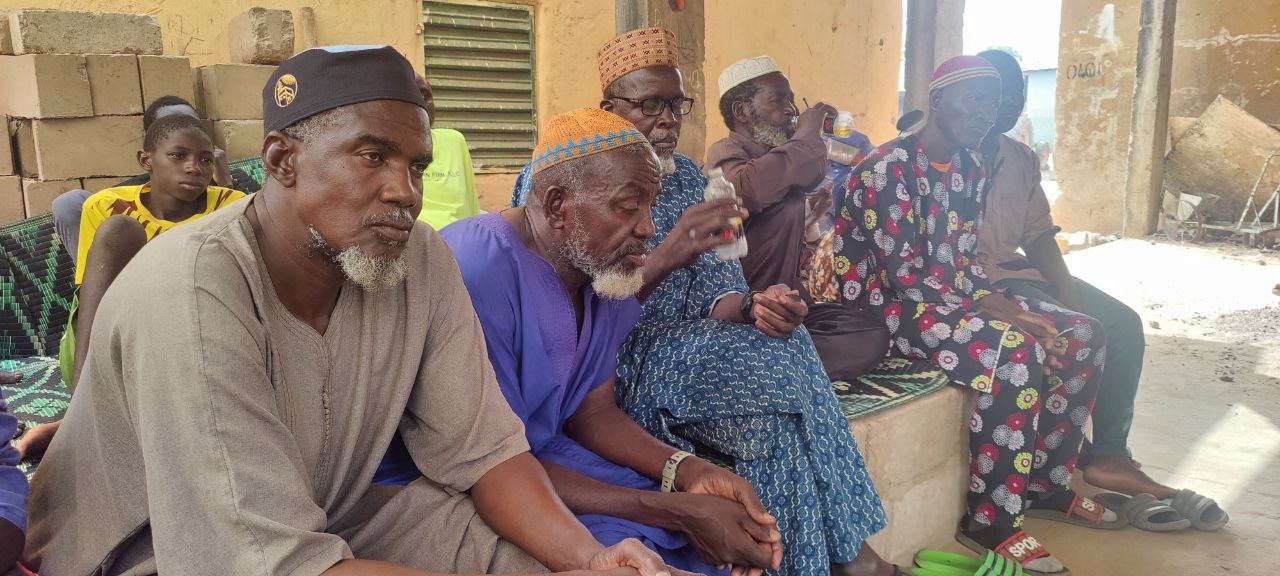

In a case called in May, 2021, Alagie Modi Trawally sued the Governor of the Upper River Region; along with the Chief Bacho Ceesay of Kantora; and Alkalo (village head), Tachine Ceesay seeking jurisdiction from the High Court concerning their human rights violations on the grounds of caste-based discrimination. Mr. Trawally, the president of One Family Group of Garawol, represented the social group mainly referred to as “The Slaves”, as opposed to the dominant “Nobles” living in the region. On behalf of the CDWD community in Gambia, this case has been supported by the Gambana International Movement through its national Secretary, Mr. Ali Camara.

Issue

The applicants' case alleged that their community – “slave” class suffers from rampant discrimination at social occasions such as funerals, weddings, naming ceremonies etc. The case asserted that the members were asked to stand at the back of the mosque to pray, which turned into outright denial once they began demanding equal rights and opportunities – breaching their constitutional right to practice their religion freely. Subsequently, they began conducting their prayers at a separate compound, before the eldest member of their group offered them land to build a mosque and school.

It is significant to note how these practices of discrimination based on a hierarchical order led to segregation of spaces. The applicants also noted that the “Nobles” denied them the use of the graveyard to bury their dead, and would even announce at funerals that the deceased person was born as an enslaved person and died as such. Moreover, this belief in an inherent “enslaved” status of the applicants' community led the dominant “Nobles” to exclude them from holding any executive position in the village associations – keeping them away from political participation and holding positions of authority.

In 2014, the applicants had held a meeting in Alkalo's compound demanding a stop to referring to them as “enslaved” people. The applicants recalled that citing traditions, the Alkalo had told them that the only way to distance themselves from being called “Slaves” is if they leave the village. The applicants note how the discrimination became further rampant after these demands – from the “Nobles” barring them from building their mosque and school to even burning one of their houses.

Citing these instances and prevalent practices, the applicants demanded the high court to order that any interference with the fundamental rights of the applicants (the so-called slave class) to freely practice their religion should amount to a violation of their constitutional rights to freely practice their religion. Henceforth, they demanded an order prohibiting the Governor, Chief and Alkalo from interfering with their right to practice their religion. Moreover, they wanted the court to declare naming them as “Slaves” as unlawful and unconstitutional.

Case laws referred:

- ANTOINE BANNA V OCEAN VIEW HOTEL & RESORT (2002-2008) 1 GLR 1

- HE STATE VS CARNEGIE MINERALS LTD & ANOR (2002-2008) 2 GLR 220 at 222

- BOURGI COMPANY LTD V WITHAMS H/V & ANOR (2002-2008) 2 GLR 31

- FIRST INTERNATIONAL BANK LTD NO.2 GAMBIA SHIPPING AGENCY LTD (2002-2008) 2 GLR 380, Holding 25 at P. 385

- HADIJATOU MANI KARAOU V THE REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ECW/CCJ/JUD/06/08

International and National Laws:

- Constitution of the Republic of the Gambia.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights

- International Convention on elimination of all forms of racial discrimination.

Judgement

Recognising Caste-based discrimination in The Gambia

Recognizing the existence of a socially stratified structure based on caste in the country, the court noted “Class-based social discrimination provenanced on the hierarchical caste system is still prevalent in The Gambia”.

It was also pointed out that this type of social discrimination is attributed to the division of labour – with gentile or landowners at the top of the hierarchy, and people working as cobblers, griots and jewellers at the very bottom. Moreover, only little research could be found in this regard.

Ruling

Citing constitutional provisions, such as Section 33(1) of the Constitution of The Republic of The Gambia, 1997 which guarantees all persons equality before the law, and its section 25(1)(c) which bestows every person the fundamental right to practice their religion – among other provisions – the court ruled in the favour of the applicants. It also cited The African Charter on Human and People's Rights, colloquially known as the “Banjul Charter”, The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Convention on Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, asserting that all human beings are born free and equal.

Henceforth, in its order, the court prohibited the respondents (Governor, Chief and Alkalo) from interfering in any way with the applicants' fundamental rights to freely practice their religion by constructing a mosque and an Arabic Islamic school.

It was further pointed out that if respondents refer to the applicants as slaves or any other title to them which conferred inferior social status for the purpose of discrimination, the same will be considered as unlawful, illegal and unconstitutional. Any related culture or practice was also declared as unlawful and illegal.

Conclusion

This story of the so-called “Slave” class/castes fighting against the imposition of an inferior caste status on their community provides a stark example of the existence of hierarchical social groups within the same race and religion and the oppressed rebelling against them – and winning. However, it is also important to note that though the High Court ruled in favour of the applicants, prohibiting their exclusion from public spaces and labelling them as “Slaves”, the practices of discrimination on the ground and the associated sense of superiority and inferiority have not ceased to exist. It is an ongoing struggle. The Gambana International Movement is one such movement working tirelessly to abolish caste based discrimination in West Africa. They encourage social groups with an inherent “slave” status to renounce it and free themselves from existing forms of slavery. They have also documented recent caste attacks and narrate several stories of atrocities which the people are courageously challenging. The Gambana movement is currently present in Gambia, Mauritania, Mali and as a diaspora in the UK and in Spain.

Evident from these instances, discrimination based on work and descent is prevalent in Africa, manifesting in ways as it does in other parts of the world – such as Europe, Latin America, and South and East Asia. It is, thus, essential that this form of discrimination is recognized by state actors, international organisations and larger civil society, and steps are taken to protect the rights of communities discriminated on work and descent.